Soviet Photo Ussr Russian Andrei Gromyko Belarus Vintage Communist

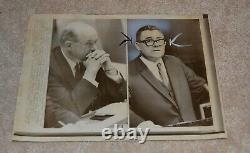

A LaserPhoto of ANDRE GROMKYO SOVIET RUSSIA MINISTER. Andrei Andreyevich Gromyko was a Soviet Belarusian communist politician during the Cold War.

He served as Minister of Foreign Affairs and as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. Gromyko was responsible for many top decisions on Soviet foreign policy until he retired in 1988. I first met Andrei Gromyko in London in 1945, where he was representing the Soviet Union on the Preparatory Commission of the United Nations.

Gromyko had been a very young wartime Soviet ambassador in Washington and was generally regarded as something of a whiz kid. Most of Gromyko's colleagues on the Preparatory Commission had worked with him on the drafting of the United Nations Charter.

The international climate was now rapidly changing, the smiles and bonhomie of San Francisco giving way to the grim realities that were soon to become the Cold War. 15 May 1947 - Starting with his involvement in the creation of the United Nations, and with his subsequent appointment as the USSR's Permanent Representative to the UN and then as the USSR's Foreign Minister, Ambassador Gromyko became a regular fixture at the world body.Shown here, in May 1947, ahead of a General Assembly meeting, he meets with Secretary-General Trygve Lie (left) and Alfred Fiderkiewicz of Poland, the Assembly's alternate Vice-President. Although some of the spirit of wartime cooperation remained, mutual suspicion and hostility between Stalin's Soviet Union and the west were growing fast.

Gromyko handled his difficult assignment with great skill. The Soviet line had become increasingly unwelcome to the other delegates, though Gromyko himself was still liked and respected.

The United States was at that time not only the richest country in the world, but also the only nuclear power. The Soviet Union had been devastated by the war, and while a permanent member of the new UN Security Council, it was physically weak and in a minority. It was Gromyko's task to reduce the appearance of this inequality as much as possible. Despite the first ominous symptoms of the Cold War, the proceedings of the UN Preparatory Commission were relatively harmonious and achieved a great deal of organizational work in an extraordinarily short time.

Some of the credit for this was certainly due to Gromyko. Dour and gruff in demeanor, his wry humor defused many difficult debates. He liked rather formulaic jokes like saying, after a long debate on a resolution, I have just one small amendment. It is to add the word'not' in the operative paragraph.

These sallies amused and relieved Gromyko's colleagues. One of Gromyko's most important interventions concerned the permanent location of the headquarters of the future UN. The Europeans and the United States favoured Geneva, from which the Soviet Union had been expelled in 1939 for invading Finland. Gromyko argued that the United States was the best place for the UN's headquarters. "The United States is located conveniently between Asia and Europe" he said.

The old world had it once and it is time for the new world to have it. The Soviet Union, remembering that in 1919 the United States had invented the League of Nations and then refused to join it, wanted to make it as difficult as possible for the US to withdraw from the new world organization.

Gromyko's pointof view prevailed, and New York became the UN's hometown. Some highlights from the career of Andrei Gromyko, the Soviet Union's top diplomat who served as Permanent Representative to the United Nations before becoming Foreign Minister, a post in which he served from 1957 to 1985 and which had him return to UN Headquarters many times over the decades. By the time the UN moved to New York City in 1952, the political atmosphere was already much bleaker, and there was notably less diplomatic banter in the daily business at the UN.

The debates in the Security Council, which initially met in the converted gymnasium of Hunter College (now Lehman College) in the Bronx, were grim affairs, often involving prolonged verbal battles between East and West. Gromyko, being in a voting minority in the Council, often had to resort to the veto, which led to much outrage in the American press.

Lady Theodosia Cadogan, the imperious wife of the British ambassador, was heard, at a public dinner, to ask in high Edwardian tones, Mr. Gromyko, why don't you stop that stupid veto? 25 September 1961 - President John F. Kennedy of the United States addressed the 16th session of the UN General Assembly. Here, at a reception given by the US Mission to the UN for heads of delegations, President Kennedy greetings Foreign Minister Gromyko of the USSR.

Gromyko created a sensation by walking out of the Security Council in protest at the debate on the presence of Soviet groups in Iran in 1946. His absence set a precedent which had unintended and far-reaching consequences. At the start of the Korean crisis in 1950, the Soviet Union was boycotting the Security Council in protest against Taiwan's representing China in the UN and was therefore unable to veto the decision to launch a UN force to counter the North Korean invasion of South Korea. After that mistake no Soviet ambassador was allowed to leave his seat at the table while the Security Council was in session, even to go to the bathroom. Gromyko remained the dominant spokesman for Soviet foreign policy until shortly before his death. This must have required enormous discipline and self-restraint. Unlike other Soviet cold warriors - Yakov Malik, Andrei Vishinsky, Valerian Zorin - Gromyko, however adversarial, was always dignified and never descended to the gutter level of abuse and name-calling often reached by the others. Soviet leaders, taking Gromyko for granted, delighted in attempting to humiliate him. The buffoon Khrushchev told a visiting foreign dignitary, That is Gromyko, my foreign minister.If I tell him to pull down his pants and sit on a block of ice, he will do it. I had my last direct contact with Gromyko in 1973. We were in Geneva for the Middle East Peace Conference after the 1973 Yom Kippur war. Secretary General Kurt Waldheim had been charged with organizing this highly publicized meeting and, as so often in such affairs, the seating arrangements presented major symbolic difficulties. We had finally come up with a plan in which the Unites States and the USSR, as the co-chairmen of the conference, would be seated as buffers between the most mutually hostile members.

This meant, among other things, that the USSR would be seated next to Israel. Henry Kissinger agreed to persuade Israel to accept this arrangement if Waldheim could get Gromyko to accept it. I was dispatched on this errand and found Gromyko in his fun-loving mood. This, he said, was a challenge he had been awaiting for twenty years.

When I said that time was very short and urged him to accept, he replied, On one condition. Henry Kissinger must ask me on his knees. I brought Kissinger over, and after much badinage Gromyko finally accepted graciously. The conference opened only forty minutes late.

26 June 1945 - Andrei Gromyko's involvement in foreign affairs began early. He joined the diplomatic service of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) at the age of 30 in 1939. He was appointed the Soviet Union's Permanent Representative to the United States in 1943, and took part in many of the international gatherings which led to the creation of the United Nations.

Here, he signs the UN Charter at the UN Conference on International Organization (also known as the San Francisco Conference given its location), which reviewed previous steps to forming the world body and the creation of the UN Charter. In meeting with style and dignity the formidable challenge of representing the Soviet Union to a largely hostile world, Gromyko became an international institution. Despite the bitter political climate, those who dealt with him from the other side of the East-West divide never lost their respect, even affection for him. Almost everyone in Old Gromyki in Belorussia in 1909 took their surname from the village's name and were called Gromyko.

So were more than 250 families in New Gromyki not far away. For practical purposes everyone needed a nickname or pseudonym, and the young Andrei Andreyevich's was Burmakov. Born into a poor peasant household he managed to get an education which took him to the Lenin Institute in Moscow. His field was economics and in his twenties he held a senior post at the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Stalin's 1930s purges, however, created promising job opportunities in the Soviet foreign service, to which Andrei Gromyko would prove ideally suited.

Rising rapidly up the system, he specialized in American affairs and in 1939 was made head of the United States section of the foreign affairs commissariat. He was a protégé of Vyacheslav Molotov, whom he would virtually succeed as foreign minister.

Meanwhile, Gromyko was appointed ambassador to Washington DC in 1943 when he was only thirty-four, and from 1946 he was the Soviet representative on the UN Security Council, in which capacity he cast his country's veto twenty-six times. In the 1950s he did a short spell as ambassador in London, where he could not bring himself to wear a top hat to Buckingham Palace to present his credentials. He was forty-five when he was made Soviet foreign minister in succession to Dmitri Shepilov, who had held the post after Molotov for only a few months.

Gromyko kept his hold on it for almost thirty years. Gromyko was a diplomat's diplomat. Whether by temperament or design, or both, he was never linked with any particular set of policies or associated with any particular faction in Soviet politics. He appeared to have no principles beyond, in the old definition of an ambassador's job,'lying abroad for his country', which he was good at. He was an unfailingly reliable spokesman for whatever it was his masters wanted said.Appointed foreign minister under Malenkov, Gromyko served through the de-Stalinization period after the dictator's death and was involved in the Cuban missile crisis and the other events of the Khrushchev years until the coming of the Gorbachev regime in 1985. By then he was well into his seventies and he was replaced as foreign minister and given the ceremonial position of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. He retired in 1988 and died the following year at seventy-nine. Andrei Gromyko was born on July 18, 1909, in a village in Belorussia, then a province in the western region of the Russian Empire.

His parents were peasant farmers. After the Revolution of 1917 the Communist state helped young people from working families to obtain a higher education and encouraged them to join the Communist Party.

Gromyko took advantage of these opportunities. Despite the hardships which the collectivization of agriculture imposed on the peasant population, he became a loyal supporter of Stalin's regime. He joined the Communist Party in 1931 and attended an agricultural technical school in his province, graduating in 1936. He then went to Moscow to work in the Institute of Economics of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, where he completed his doctoral thesis on the mechanization of agriculture in the United States.

For several years he occupied the position of senior researcher in the institute, where he specialized in the American economy. He began a new career in 1939 in the Soviet Diplomatic Service.

Many older diplomats had disappeared during the late 1930s in Stalin's police terror. The new recruits who took their place received quick promotion to important diplomatic positions. Gromyko had the necessary qualifications for advancement. Son of working peasants, well educated, and a member of the party since the beginning of the Stalin take-over, he belonged to the new generation of Stalinists. He had no experience or previous training in international relations.

He learned his leadership skills on the job. Until 1985 his entire career was devoted to Soviet foreign affairs. Gromyko began his work at the Soviet embassy in Washington, D.

One of the Soviet Union's most important diplomatic posts. In 1943 at age 34 he was made Soviet ambassador to the United States. While serving in Washington he learned to speak fluent English. In World War II the Soviet Union and the United States were allies against Nazi Germany and Japan. Gromyko attended the major Allied conferences at Yalta and Potsdam in 1945, assisting Stalin in his negotiations with US leaders.

The Soviet Union that year joined in the founding of the United Nations. Gromyko participated in the writing of the U.Charter, which made the Soviet Union a member of the Security Council with the right to veto any U. In 1946 he became the permanent representative from the USSR to the Security Council. In the two years that followed, the beginning of the Cold War produced serious diplomatic conflicts in the United Nations between the Soviet Union and the West. Gromyko faithfully carried out the new Soviet policy, casting 26 vetoes to prevent the United Nations from adopting resolutions of which Stalin disapproved.

His unsmiling public appearances earned him the title among Western diplomats of Old Stone Face. His work satisfied Stalin and Molotov, minister of foreign affairs, and in 1949 he was promoted to first deputy minister, becoming Molotov's direct assistant. In ten years he had risen from the position of research scholar in agriculture to one of the most important posts in Soviet foreign relations. After Stalin's death in 1953 Gromyko continued to serve the new leaders competently and loyally. When Khrushchev came to power in 1955 he introduced a policy of "peaceful coexistence" to improve relations with the West.New conferences were held between East and West. Gromyko collaborated in these meetings.

His influence grew when in 1956 he was appointed a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. His career advanced again in 1957 when the minister of foreign affairs joined a group of other leading Communists opposing Khrushchev's policies in an attempt to remove him from power. They failed and were themselves removed from their leadership positions (Molotov left Moscow to become Soviet ambassador to the Mongolian People's Republic). Gromyko's reward for loyal service and for taking no part in the plot to depose Khrushchev was promotion to minister of foreign affairs. In his years as minister he distinguished himself by his ability to implement effectively the policies of the Soviet leadership.

He was adept at accommodating every Soviet leader from Stalin to Gorbachev, and in dealing with nine US presidents during his career. He participated actively in all international meetings and negotiated with leaders of important countries.In 1962 Khrushchev secretly ordered the installation of Soviet intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Cuba. Gromyko went to Washington at that time to talk with President Kennedy, who warned him of the danger of a US-Soviet war if the Soviet missiles were actually placed in Cuba.

Gromyko never admitted that his country was involved in this dangerous action; later he claimed that he had not concealed the move since the US president had never put the question of the missiles directly to him. In the mid-1960s the Soviet Union began major industrial projects with the aid of Western corporations, including the Fiat automobile company in Italy. In 1966 Gromyko led the Soviet delegation to Rome to conclude the Fiat agreement. There he asked for and received an audience with the Pope. He was the first Soviet statesman publicly to recognize the importance of the Papacy. He appeared to have felt a deep satisfaction at the growing power and influence of his country in world affairs, asserting in 1971 that today there is no question of any significance (in international relations) which can be resolved without the Soviet Union or in opposition to her. Gromyko belonged to the Soviet political elite who enjoyed special comforts and privileges. He took personal pleasure in fine clothes, having his business suits specially made by Western tailors. He was probably instrumental in the successful career of his son, who became director of the Institute of African Affairs and wrote many authoritative articles on Soviet foreign policy (one consisting of a rare interview with his father discussing the Cuban missile crisis). A Power In The Politburo.In the early 1970s the Soviet Union concluded with the United States an important treaty for the limitation of nuclear armaments, the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT). Gromyko helped to negotiate the final agreement. He acquired extensive knowledge of ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons.

When negotiating, noted one observer, Gromyko never took a note, never looked at a folder or turned to his assistants for advice. His service in these negotiations and support for the Soviet leader, Brezhnev, earned him in 1973 a position in the Communist Party's ruling committee, the Politburo. In addition, he received during his years as foreign minister many honors, including the Order of Lenin and Hero of Socialist Labor. Relations with the United States gradually worsened during the 1970s. Gromyko sought in international meetings to strengthen the global influence of the Soviet Union.

He promoted close ties with African states regardless of their type of government or economic system, declaring that we do not consider ideological differences in social systems. When in the early 1980s Brezhnev became ill and could not make major foreign policy statements, Gromyko took his place. In the campaign to prevent the United States from placing new nuclear missiles in Europe, he declared in 1982 in the United Nations that the Soviet Union, "the world's foremost peace loving nation, " promised never to be the first state in any international conflict to use nuclear weapons. This "no first use" pledge did not represent a new policy, for the Soviet Union had built its nuclear weapons arsenal to match that of the United States and to prevent a nuclear attack. In making the speech Gromyko established that he had begun to play a major part in decisions on Soviet foreign policy. His decades of experience in international relations had by then earned him a new title-Dean of World Diplomacy. The Rise Of Gorbachev And The Demise Of. After Brezhnev's death in late 1982 Gromyko became one of the small circle of Soviet Communists in the Politburo to choose the new Soviet leader. Two successors died soon after their appointments.In 1985 the Politburo picked their youngest member, Mikhail Gorbachev, to be general secretary. Gromyko made the formal announcement of this choice. He occupied by then the informal position among his colleagues as senior member of the Politburo.

Gorbachev elevated Gromyko's position to that of President, the official title being Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, thus replacing Chernenko, who had died in March, 1985. This position, though prestigious, lacked an effective degree of power, and essentially brought Gromyko's political career to an end after 28 years.

Gromyko was replaced as Minister of Foreign Affairs by Eduard Shevardnadze, former party boss of the Soviet Republic of Georgia. In 1989, the Politburo voted Gromyko out as president. He was hospitalized for vascular problems shortly thereafter, and died in July 1989, at the age of 80. Only one Politburo member attended his funeral.Gromyko's autobiography Memoirs was begun in 1979, published in the Moscow in 1988 and in the US in 1990. There are countless discrepancies between events, not only in the nine years it took Gromyko to write the book, but also in the later English translation.

In his autobiography, Gromyko recounts meetings with everyone from Marilyn Monroe to Yasar Arafat to Pope John Paul II. Although he reveals little, Gromyko remained a loyal Stalinist to the end. Despite recent reassessment of Stalin's career and methodologies, Gromyko stubbornly defends him. With regard to the Cold War, Gromyko blames the US and holds Stalin himself blameless. Summary biographies are included in Who's Who in the Soviet Union (1984) and in The International Who's Who 1984-85 (1984); brief biographical accounts of his life are provided in "A Diplomat for All Seasons, " TIME (June 25, 1984); "Winds of Kremlin Change, " TIME (July 15, 1985); in various book reviews of Memories:see New Republic (May 14, 1990); and National Review (April 30, 1990); and in "An Enduring Russian Face, " New York Times (July 3, 1985); scattered references to his activity as minister of foreign affairs are found in Robin Edmunds, Soviet Foreign Policy:The Brezhnev Years (1983); Gromyko's memoirs, titled Memories, were published in 1990.

Andrei Gromyko was born into a peasant family in the village of Starye Gromyki in Belorussia. He joined the Communist Party in 1931.He completed study at the Minsk Agricultural Institute in 1932 and gained a Candidate of Economics degree from the All-Union Scientific Research Institute of Agronomy in 1936. From 1936 to 1939 he was a senior researcher in the Institute of Economics of the Academy of Sciences and the executive editorial secretary of the journal Problemy ekonomiki; he later gained a doctorate of Economics in 1956. In 1939 Gromyko switched to diplomatic work and became section head for the Americas in the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs. Later that year he became counselor in the Soviet Embassy in Washington.

Between 1943 and 1946 he was Soviet ambassador to the United States and Cuba. During this time, he was involved in the Dumbarton Oaks Conference (1944) called to produce the UN Charter and the 1945 San Francisco conference establishing the United Nations. He also played an organizational role in the Big Three wartime conferences. From 1946 to 1948 he was the permanent representative in the UN Security Council as well as deputy (from 1949 First Deputy) minister of foreign affairs.

Gromyko remained foreign minister until July 1985, when he became chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, effectively Soviet president. Throughout his career, Gromyko was neither highly ambitious nor a major political actor on the domestic scene.

Although a full member of the Central Committee from 1956, he did not become a full member of the Politburo until 1973. He developed his diplomatic skills and became the public face of Soviet foreign policy, gaining a reputation as a tough negotiator who never showed his hand. He was influential in the shaping of foreign policy, in particular détente, but he was never unchallenged as the source of that policy; successive leaders. Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev both sought to place their personal stamp upon foreign policy, while there was always competition from the International Department of the Party Central Committee and the KGB.Gromyko formally nominated Mikhail Gorbachev as General Secretary in March 1985, and three months later was moved from the Foreign Ministry to the presidency. The foreign policy for which he was spokesperson during the Brezhnev period now came under attack as Gorbachev and his Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze embarked on a new course. Gromyko's most important task while he was president was to chair a commission that recommended the removal of restrictions on the ability of Crimean Tatars to return to Crimea.

Gromyko was forced to step down from the Politburo in September 1988, and from the presidency in October 1988, and was retired from the Central Committee in April 1989. He was the author of many speeches and articles on foreign affairs.See also: brezhnev, leonid ilich; gorbachev, mikhail sergeyevich. Soviet Foreign Policy: The Brezhnev Years. The Elite of the USSR Today. Encyclopedia of Russian History GILL, GRAEME.

Gromyko, Andrei (1909-89) Soviet statesman, foreign minister (1957-85), president (1985-88). As Soviet ambassador to the USA (1943-46), Gromyko took part in the Yalta and Potsdam peace conferences (1945).

He acted as the permanent Soviet delegate to the United Nations (1946-48). As foreign minister, Gromyko represented the Soviet Union throughout most of the Cold War and helped to arrange the summits between Brezhnev and Nixon. He was given the largely honorary role of president by Mikhail Gorbachev. 5 July 1909 - 2 July 1989[2] was a Soviet Belarusian communist politician during the Cold War.

In the 1940s Western pundits called him Mr. No" or "Grim Grom, because of his frequent use of the Soviet veto in the United Nations Security Council.Gromyko's political career started in 1939 with his employment at the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs (renamed Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1946). He became the Soviet ambassador to the United States in 1943, leaving that position in 1946 to become the Soviet Permanent Representative to the United Nations.

Upon his return to the Soviet Union he became a Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs and later the First Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs. He went on to become the Soviet ambassador to the United Kingdom in 1952. During his tenure as Foreign Minister of the Soviet Union, Gromyko was directly involved in the Cuban Missile Crisis and helped broker a peace treaty ending the 1965 Indo-Pakistani War. Under Leonid Brezhnev's leadership, he played a central role in the establishment of detente with the United States through his negotiation of the ABM Treaty, the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, and SALT I & II, among others.

After Brezhnev suffered a stroke in 1975 impairing his ability to govern, Gromyko formed a troika with KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov and Defense Minister Dmitriy Ustinov that dominated Soviet policymaking during the final years of Brezhnev's regime. Henceforth, Gromyko's conservatism and pessimistic view of the West dictated Soviet diplomacy until the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985. Following Gorbachev's election as General Secretary, Gromyko lost his office as foreign minister and was appointed to the largely ceremonial office of head of state. Subsequently, he retired from political life in 1988, and died the following year in Moscow. Ambassador and World War II. At the helm of Soviet foreign policy. Soviet ambassador to the United Kingdom. Foreign Minister of the Soviet Union. Head of state, retirement and death. Gromyko was born to a poor "semi-peasant, semi-worker" Belarusian family[3] in the Belarusian village of Staryya Gramyki, near Gomel on 18 July 1909. Gromyko's father, Andrei Matveyevich, worked as a seasonal worker in a local factory. Andrei Matveyevich was not a very educated man, having only attended four years of school, but knew how to read and write.[4] Gromyko's mother, Olga Yevgenyevna, came from a poor peasant family in the neighbouring city of Zhelezniki. She attended school only for a short period of time as, when her father died, she left to help her mother with the harvest. Gromyko grew up near the district town of Vetka where most of the inhabitants were devoted Old Believers in the Russian Orthodox Church. [6] Gromyko's own village was also predominantly religious, but Gromyko started doubting the supernatural at a very early age. His first dialog on the subject was with his grandmother Marfa, who answered his inquiry about God with Wait until you get older.

Then you will understand all this much better. According to Gromyko, "Other adults said basically the same thing" when talking about religion. Gromyko's neighbour at the time, Mikhail Sjeljutov, was a freethinker and introduced Gromyko to new non-religious ideas[7] and told Gromyko that scientists were beginning to doubt the existence of God. From the age of nine, after the Bolshevik revolution, Gromyko started reading atheist propaganda in flyers and pamphlets. [8] At the age of thirteen Gromyko became a member of the Komsomol and held anti-religious speeches in the village with his friends as well as promoting Communist values. The news that Germany had attacked the Russian Empire in August 1914 came without warning to the local population. This was the first time, as Gromyko notes, that he felt "love for his country". His father, Andrei Matveyevich, was again conscripted into the Imperial Russian Army and would serve for three years on the southwestern front, under the leadership of General Aleksei Brusilov. Gromyko was elected First Secretary of the local Komsomol chapter at the beginning of 1923. [11] Following Vladimir Lenin's death in 1924, the villagers asked Gromyko what would happen in the leader's absence. Gromyko remembered a communist slogan from the heyday of the October Revolution: The revolution was carried through by Lenin and his helpers." He then told the villagers that Lenin was dead but "his aides, the Party, still lived on. When he was young Gromyko's mother Olga told him that he should leave his home town to become an educated man.

[13] Gromyko followed his mother's advice and, after finishing seven years of primary school and vocational education in Gomel, he moved to Borisov to attend technical school. Gromyko became a member of the All-Union Communist Party Bolsheviks in 1931, something he had dreamed of since he learned about the "difference between a poor farmer and a landowner, a worker and a capitalist". Gromyko was voted in as secretary of his party cell at his first party conference and would use most of his weekends doing volunteer work. [12] Gromyko received a very small stipend to live on, but still had a strong nostalgia for the days when he worked as a volunteer.

It was about this time that Gromyko met his future wife, Lydia Dmitrievna Grinevich. Grinevich was the daughter of a Belarusian peasant family and came from Kamenki, a small village to the west of Minsk. [14] She and Gromyko would have two children, Anatoly and Emiliya. After studying in Borisov for two years Gromyko was appointed principal of a secondary school in Dzerzhinsk, where he taught, supervised the school and continued his studies. One day a representative from the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Byelorussia offered him an opportunity to do post-graduate work in Minsk. [16] Gromyko traveled to Minsk for an interview with the head of the university, I. Borisevich, who explained that a new post-graduate program had been formed for training in economics; Gromyko's record in education and social work made him a desirable candidate. Gromyko advised Borisevich that he would have difficulty living on a meager student stipend. Borisevich assured him that on finishing the program, his salary would be at the party's top pay grade - "a decent living wage".Gromyko accepted the offer, moving his family to Minsk in 1933. Gromyko and the other post-graduates were invited to an anniversary reception [17] at which, as recounted in Gromyko's Memoirs. We were amazed to find ourselves treated as equals and placed at their table to enjoy what for us was a sumptuous feast. We realised then that not for nothing did the Soviet state treat its scientists well: evidently science and those who worked in it were highly regarded by the state.

After that day of pleasantry, Gromyko for the first time in his life wanted to enter higher education, but without warning, Gromyko and his family were moved in 1934 to Moscow, settling in the northeastern Alexeyevsky District. [18] In 1936, after another three years of studying economics, Gromyko became a researcher and lecturer at the Soviet Academy of Sciences.

His area of expertise was the US economy, and he published several books on the subject. Gromyko assumed his new job would be a permanent one, but in 1939 he was called upon by a Central Committee Commission which selected new personnel to work in diplomacy. The Great Purge of 1938 opened many positions in the diplomatic corps. Gromyko recognised such familiar faces as Vyacheslav Molotov and Georgy Malenkov. A couple of days later he was transferred from the Academy of Sciences to the diplomatic service.

Andrei Gromyko (second from left) at Yalta in February 1945. In early 1939, Gromyko started working for the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs in Moscow.Gromyko became the Head of the Department of Americas and because of his position Gromyko met with United States ambassador to the Soviet Union Lawrence Steinhardt. Gromyko believed Steinhardt to be "totally uninterested in creating good relations between the US and the USSR"[20] and that Steinhardt's predecessor Joseph Davies was more "colourful" and seemed "genuinely interested" in improving the relations between the two countries. [21] Davies received the Order of Lenin for his work in trying to improve diplomatic relations between the US and the USSR. After heading the Americas department for 6 months, Gromyko was called upon by Joseph Stalin. Stalin started the conversation by telling Gromyko that he would be sent to the Soviet embassy in the United States to become second-in-command.

"The Soviet Union, " Stalin said, "should maintain reasonable relations with such a powerful country like the United States, especially in light of the growing fascist threat". Vyacheslav Molotov contributed with some minor modifications but mostly agreed with what Stalin had said. [22] How are your English skills improving? " Stalin asked, "Comrade Gromyko you should pay a visit or two to an American church and listen to their sermons.

Priests usually speak correct English with good accents. Do you know that the Russian revolutionaries when they were abroad, always followed this practice to improve their skills in foreign languages? Gromyko was quite amazed about what Stalin had just told him but he never visited an American church.[24] He later wrote in his Memoirs that New York City was a good example on how humans, by the "means of wealth and technology are able to create something that is totally alien to our nature". He further noticed the New York working districts which, in his own opinion, were proof of the inhumanity of capitalism and of the system's greed. [25] Gromyko met and consulted with most of the senior officers of the United States government during his first days[26] and succeeded Maxim Litvinov as ambassador to the United States in 1943.

In his Memoirs Gromyko wrote fondly of President Franklin D. Roosevelt[27] even though he believed him to be a representative of the bourgeoisie class. [28] During his time as ambassador, Gromyko met prominent personalities such as British actor Charlie Chaplin, [29] American actress Marilyn Monroe[30] and British economist John Maynard Keynes. Gromyko was a Soviet delegate to the Tehran, Dumbarton Oaks, Yalta and Potsdam conferences.[32] In 1943, the same year as the Tehran Conference, the USSR established diplomatic relations with Cuba and Gromyko was appointed the Soviet ambassador to Havana. [33] Gromyko claimed that the accusations brought against Roosevelt by American right-wingers, that he was a socialist sympathizer, were absurd.

[34] While he started out as a member delegate Gromyko later became the head of the Soviet delegation to the San Francisco conference after Molotov's departure. Gromyko was appointed Permanent Representative of the Soviet Union to the United Nations (UN) in April 1946. [36] The USSR supported the election of the first Secretary-General of the United Nations, Trygve Lie, a former Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs. However, in the opinion of Gromyko, Lie became an active supporter of the "expansionist behaviour" of the United States and its "American aggressionist" policy. Because of this political stance, Gromyko believed Lie to be a poor Secretary-General.

[37] Trygve's successor, Swede Dag Hammarskjöld also promoted what Gromyko saw as "anti-Soviet policies". [38] U Thant, the third Secretary-General, once told Gromyko that it was close to impossible to have an objective opinion of the USSR in the Secretariat of the United Nations because the majority of secretariat members were of American ethnicity or supporters of the United States. [39] Gromyko often used the Soviet veto power in the early days of the United Nations. So familiar was a Soviet veto in the early days of the UN that Gromyko became known as Mr Nyet, literally meaning "Mr No". During the first 10 years of the UN, the Soviet Union used its veto 79 times.

In the same period, the Republic of China used the veto once, France twice and the others not at all. [40] On May 14, 1947, Gromyko advocated the one-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and the two-state solution as the second best option in the case that relations between the Jewish and Arab populations of Palestine...

Proved to be so bad that it would be impossible to reconcile them. Gromyko was appointed Soviet ambassador to the United Kingdom at a June 1952 meeting with Joseph Stalin in the Kremlin. Stalin paced back and forth as normal, telling Gromyko about the importance of his new office, and saying The United Kingdom now has the opportunity to play a greater role in international politics. But it is not clear in which direction the British government with their great diplomatic experience will steer their efforts... This is why we need people who understand their way of thinking. Gromyko met with Winston Churchill in 1952 not to talk about current politics but nostalgically about World War II. Gromyko met Churchill again in 1953 to talk about their experiences during World War II before returning to Russia when he was appointed Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs. L-R: Batsanov, Llewellyn Thompson, Gromyko and Dean Rusk in 1967 during the Glassboro Summit Conference. Andrei Gromyko spent his initial days as Minister of Foreign Affairs solving problems between his ministry and the International Department (ID) of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) headed by Boris Ponomarev. Ponomarev advocated an expanded role for the ID in Soviet foreign relations; Gromyko flatly refused it.Valentin Falin, a top Soviet official, said the ID "interfered in the activities" of Gromyko and his ministry countless times. Gromyko disliked both Ponomarev and the power sharing between the ID and the foreign ministry. [43] In 1958 Mao Zedong tried to look for supporters within the Soviet leadership for his planned war with the Republic of China (Taiwan). He flabbergasted Gromyko by telling him that he was willing to sacrifice the lives of "300 million people" just for the sake of annexing the Republic of China into the People's Republic of China. Gromyko assured Mao that the proposal would never get the approval of the Soviet leadership.

When the Soviet leadership learnt of this discussion they responded by terminating the Soviet-Chinese nuclear program and various industrialization projects in the People's Republic of China. [44] Years later during the Cuban Missile Crisis, Gromyko met John F. Kennedy, then President of the United States, while acting on the instruction of the Soviet leadership under Nikita Khrushchev.

In his Memoirs, Gromyko wrote that Kennedy seemed out of touch when he first met him, and was more ideologically driven than practical. In a 1988 interview, he further described Kennedy as nervous and prone to making contradictory statements involving American intentions towards Cuba.

During his twenty-eight years as Minister of Foreign Affairs Gromyko supported the policy of disarmament, stating in his Memoirs that "Disarmament is the ideal of Socialism". Gromyko meeting with Jimmy Carter, the President of the United States, in 1978. Throughout his career as Soviet Foreign Minister, Gromyko explicitly promoted the idea that no important international agreement could be reached without the Soviet Union's involvement.

[46] One accomplishment he took particular pride in was the signing of the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty whose negotiation could be traced back to 1958. Additionally, in 1966, Gromyko and Alexei Kosygin persuaded both Pakistan and India to sign the Tashkent Declaration, a peace treaty in the aftermath of the Indo-Pakistan war of 1965. Later in the same year, he engaged in a dialog with Pope Paul VI, as part of the pontiff's ostpolitik that resulted in greater openness for the Roman Catholic Church in Eastern Europe[47] although there was still heavy persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union. [48] Gromyko also prided himself on the signing of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons on 1 July 1968, the 1972 ABM and SALT I treaties, and the Agreement on the Prevention of Nuclear War in 1973. After joining the Politburo in 1973 during Leonid Brezhnev's rule, Gromyko steadily consolidated his position in the party hierarchy to become the Soviet Union's chief foreign policy strategist. [49] Upon reaching the peak of his power and influence, Gromyko's approach to diplomacy began to suffer from the same qualities that underpinned his early career. His exceptional memory and confidence in his experience now made him inflexible, unimaginative and devoid of a long-term vision for his country. [50] By the time Andropov and Chernenko rose to the Soviet leadership, Gromyko frequently found himself advocating a harder line than his superiors. Andrei Gromyko speaking at the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, in 1984. As Brezhnev grew increasingly incapable of governing following a stroke in 1975, Gromyko formed a de facto troika with KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov and Defense Minister Dmitry Ustinov that became the driving force behind Soviet policymaking.[51] After Brezhnev's death in 1982, Andropov was voted in as General Secretary by the Politburo. Immediately after his appointment Andropov asked Gromyko if he wanted to take over Brezhnev's old office of the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. Gromyko turned down Andropov's offer, believing that Andropov would eventually take the office for himself. After Chernenko's death in 1985, Gromyko nominated Mikhail Gorbachev for the General Secretary on 11 March 1985. In supporting Gorbachev, Gromyko knew that the influence he carried would be strong.

[53] After being voted in Gorbachev relieved Gromyko of his duty as foreign minister and replaced him with Eduard Shevardnadze and Gromyko was appointed to the largely honorary position of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. A Belarusian stamp from 2009 depicting Gromyko.

Gromyko held the office of the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, literally head of state, which was largely ceremonial, and his influence in ruling circles diminished. A number of First World journalists believed Gromyko was uncomfortable with many of Gorbachev's reforms, [55] however, in his Memoirs Gromyko wrote fondly of Gorbachev and the policy of perestroika.Gromyko believed that perestroika was about working for the construction of a socialist society[56] and saw glasnost and perestroika as an attempt at making the USSR more democratic. During a party conference in July 1988 Vladimir Melnikov called for Gromyko's resignation.

Melnikov blamed Brezhnev for the economic and political stagnation that had hit the Soviet Union and, seeing that Gromyko, as a prominent member of the Brezhnev leadership, was one of the men which had led the USSR into the crisis. [58] Gromyko was promptly defended as "a man respected by the people" in a note by an anonymous delegate. [59] After discussing it with his wife Gromyko decided to leave Soviet politics for good.

Gromyko recounts in his Memoirs that he told Gorbachev that he wished to resign before he made it official. The following day, 1 October 1988, Gromyko sat beside Gorbachev, Yegor Ligachev and Nikolai Ryzhkov in the Supreme Soviet to make his resignation official:[60]. Such moments in life are just as memorable as when one is appointed to prominent positions. When my comrades took farewell to me, I was equally moved as I had ever been when I was given an important office.

This memory is very precious to me. Gorbachev succeeded Gromyko in office as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. [61] After his resignation Gorbachev praised Gromyko for his half-century of service to USSR. Critics, such as Alexander Belonogov, the Permanent Representative of the Soviet Union to the United Nations, claimed Gromyko's foreign policy was permeated with "a spirit of intolerance and confrontation". After retiring from active politics in 1989 Gromyko started working on his memoirs.

[63] Gromyko died on 2 July 1989, days before what would have been his 80th birthday, after being hospitalised for a vascular problem that was not further identified. His death was followed by a minute of silence at the Congress of People's Deputies to commemorate him. The Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS), the central news organ in the USSR, called him one of the country's most "prominent leaders". President of the United States George H.

Bush sent his condolences to Gromyko's son, Anatoly. [64] Gromyko was offered a grave in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis, but at the request of his family he was not buried near the Kremlin wall but instead at the Novodevichy cemetery. Having been a person of considerable stature during his life Gromyko held an unusual combination of personal characteristics. Some were impressed by his diplomatic skills, while others called Gromyko mundane and boring. [66] An article written in 1981 in The Times said, He is one of the most active and efficient members of the Soviet leadership.

A man with an excellent memory, a keen intellect and extraordinary endurance... Maybe Andrey is the most informed Minister for Foreign affairs in the world. [63] Gromyko's dour demeanour was shown clearly during his first term in Washington and echoed throughout his tenure as Soviet foreign minister.

Yost, who worked with Gromyko at the Dumbarton Oaks Conference, the UN founding conference, and at the United Nations, recalled that the "humorless" Soviet ambassador looked as though he was sucking a lemon. "[67] There is a story that Gromyko was leaving a Washington hotel one morning and was asked by a reporter; "Minister Gromyko, did you enjoy your breakfast today? During his twenty-eight years as minister of foreign affairs Gromyko became the "number-one" on international diplomacy at home, [69] renowned by his peers to be consumed by his work. Henry Kissinger once said "If you can face Gromyko for one hour and survive, then you can begin to call yourself a diplomat". Gromyko's work influenced Soviet and Russian ambassadors such as Anatoly Dobrynin.Mash Lewis and Gregory Elliott described Gromyko's main characteristic as his "complete identification with the interest of the state and his faithful service to it". According to historians Gregory Elliot and Moshe Lewin this could help explain his so-called "boring" personality and the mastery of his own ego. [70] West German politician Egon Bahr, when commenting on Gromyko's memoirs, said;[70]. He has concealed a veritable treasure-trove from future generations and taken to the grave with him an inestimable knowledge of international connection between the historical events and major figures of his time, which only he could offer. What a pity that this very man proved incapable to the very end of evoking his experience.

As a faithful servant of the state, he believed that he should restrict himself to a sober, concise presentation of the bare essentials. On 18 July 2009, Belarus marked the 100th anniversary of Gromyko's birth with nationwide celebrations. In the city of his birth many people laid flowers in front of his bust. A ceremony was held attended by his son and daughter, Anatoly and Emiliya.

Several exhibitions were opened and dedicated to his honour and a school and a street in Gomel were renamed in honour of him. Twice Hero of Socialist Labour (1969, 1979). Seven Orders of Lenin (incl 1945).

Order of the Red Banner (9 November 1948). Order of the Badge of Honour. State Prize of the USSR (1984) - for the monograph "The external expansion capital: Past and Present" (1982).

Jubilee Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary since the Birth of Vladimir Il'ich Lenin". Grand Cross of the Order of the Sun (Peru). Order of the Sun of Freedom (Afghanistan). Andrei Gromyko, the son of peasants, was born near Minsk in Russia in 1909. After studying agriculture and economics he became a research scientist at the Soviet Academy of Science.

He later joined the diplomatic service and went to Washington during the Second World War. In 1943 Gromyko was appointed as the Soviet ambassador in the United States. In this post he attended the conferences in Teheran, Yalta and Potsdam. After the war he was made the Soviet permanent delegate to the United Nations.

He also served as ambassador to Britain (1952-53). Gromyko became Foreign Minister in 1957. He held the post for 28 years and during this period was the main Soviet negotiator with the United States government.

George Brown met Gromyko when he was serving as the British foreign secretary (1966-68): Gromyko was no politician and I always thought really just another exceedingly able party official. He, of course, did know the outside world and did not mind letting his sense of humour show or letting his hair down on occasion. His capacity to discuss and argue was to me very impressive, but, again, getting much out of him was a very tough business indeed and in my time certainly never happened again without the interval and the obvious line-clearing elsewhere.

While I was at the Foreign Office it seemed to me that Gromyko was growing in importance. His influence seemed to be becoming stronger and he probably was playing a much bigger role than before in the apparatus by which decisions were made, and was becoming much less simply the machine for carrying them out. Mikhail Gorbachev appointed Gromyko President of the Soviet Union in 1987. Andrei Gromyko died two years later, at the age of 80.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION. Committee; Minister of Foreign Affairs. COUNTRY FILES FOR EUROPE AND CANADA.

Scanned from the NSA Presidential Country Files for Europe and Canada Box 16 - USSR (2) at the Gerald R. Manager of one of th. World's largest Foreign service bureaucracies, is the most.Senior diplomatic leader among the major. Appointed in 1957, he is the first. Soviet Foreign Minister to have receive'd all of. His, dip19matic training under the communist. During his rise to the top of his profession, he has held some of his government's.

Roost demanding foreign posts: Ambassador to the. United States, Ambassador to Great'Britain and Peanent Representative to tlie united Nations. IBis ability and diligence were rewarded. L1-n---lP-rill973, when he became, the'fifth soviet. Foreign Minister--and the first career diplomat-.To be elected to the ruling Politburo of the Communist party of the soviet union (CPSU).. Earlier Foreign Ministers on that body Leon Trotskiy.

Vyacheslav Molotov, Audrey vyshinskiy and Dmitriy Shepilov were either old Bolsheviks. The full significance of Gromyko·s appointment. As it relates to a political realignment in the. Wmt POi1TV'':: C'f"v",,, ::r.. Reason for the promotion, however, probably was.

An increased recognition among Politburo members. Of the importance of foreign policy and the ex. Tent to which it impinges on domestic affairs. Groroyko's new position gives him greater poli.

Tical weight and prestige in the conduct of. Born on 18 July 1909 in a rural district. Near Gomel', Belorussian SSR, Andrey Andreyevich.

Gromyko rose from obscurity because of his. To· absorb the education that was available under. Peasants, he began his studies at an agricultural sc. Iool in Gomel l, went on to the Borisov Pedagogical Institute, and then attended the Minsk.

Gromyko then went to Moscow to con:tinue his. He studied at the Institute of Economics and was awarded a candidate of economic. Sciences degree in 1936; by which time he was also secreary of he editorial board of the USSR's. National economic journal, Voprosy Ekonomiki.

He served as a senior. Instructor at the Institute of Economics from. Gromyko apparently never lost his. The Foreign Service assignments of his new career.He earned a doctorate of economic sciences. In 1939 Gromyko joined the Foreign Service.

Became chief of the American Countries Division. Of the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs. And was assigned to'1ashingtonas Counselor of. The Soviet Embassy_ He had never been abroad. Before and spoke no English/ but 4 years later. At the age of 34, he succeeded 11aksim Litvinov as. Ambassador to the United States. In 1946 Gromyko was appointed a Deputy Foreign. Minister and the Permanent Representative to the. United Nations, where he gained international notoriety through his frequent vetoes and IIwakouts.In support of the USSR's policies. 1946-49 period he attended most of the important.

Conferences of the time, including those held at. Yalta, Dumbarton Oaks, San Francisco, London. In 1949 Grornyko was recalled to Moscow and. Appointed First Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs. He held that position until 1957, with the excep tion of a period from 1952 to 1953, when he served.

As Ambassador to the: United Kingdom. IGromyko I s assignment to.

London was not a setback for him personally but. Was part of an effort by the USSR to strengthen. Relations with the United Kingdom while weakening. British ties with the Uni ted States. Moscow did not name a replacement for Gromyko as.First Deputy Foreign Minister in. As a major spokesman on Soviet foreign policy·. Since becoming Foreign Minister in 1957 1 Gromyko.

Has led an extremely a9tive professional life. Has participated in numerous international conferences and bilateral negotiations, and he has headed. Soviet delegation to the UN General Assembly. And later Kosygin and Brezhnev on almost all of.Delegation during the tripartite talks leading to. The signing in August 1963 of a nuclear test ban. Visited Paris, paving the way for closer Franco-Soviet relations. In 1969, in a speech given before.

Soviet, he was the first high-level soviet official to call for closer US-USSR relations. Took part in negotiating the Indo-soviet Friendship Treaty in 1971, and in 1972 he came to the. United States to sign the ABM Treaty. #_ Gromyko participated in President'Nixon's talks. With Brezhnev in Moscow in May 1972 and in th'e.

United States in July 1973. Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in. Washington in February 1974 and had subsequent meetings with the Secretary in Moscow (March), Washington.

(March), Geneva (April), and Nicosia and Damascus (My). , e 1S a skilled negot1ator an a master 0 par. He has a prodigious capacity for.

Work, puttin in strenuus 6-day weeks for long, periods. He speaks fluent French and English. Arid uses American idiomatic expressions w. One of the est trave e. W1ves 1n e soviet leadership group, Mrs.

Gromyko is, at ease among foreigners. Formerly a teacher, she now is primarily. In politics and literature and is partilarly.The Gromykos have'a son and a daugblber. Y, studied in the United States and. Served at one time as a section chief at the. Institute of the USA in Moscow.

A iviinister Counselor of the Soviet Embapsy in. Anatoliy has been married brice and. Has to sons--one, born in about 1959, by his. First ife, and another, born· in about 1967, by.Is married to Aleksandr S. Ministry legal expert who is te Soviet Permanent. Gromyko (4 July 1950) The events now taking place in Korea broke out on June 25 as the result of a provocative attack by the troops of the South Korean authorities on the frontier areas of the Korean People's Democratic Republic. This attack was the outcome of a premeditated plan. From time to time Syngman Rhee himself and other representatives of the South Korean authorities had blurted out the fact that the South Korean Syngman Rhee clique had such a plan.

As long ago as October 7, 1949, Syngman Rhee, boasting of success in training his army, stated outright, in an interview given to an American United Press correspondent, that the South Korean Army could capture Pyongyang in the course of three days. On October 31, 1949, Sin Sen Mo, Defence Minister of the Syngman Rhee Government, also told newspaper correspondents that the South Korean troops were strong enough to act and take Pyongyang within a few days. Only one week before the provocative attack of the South Korean troops on the frontier areas of the Korean People's Democratic Republic, Syngman Rhee said, in a speech on June 19 in the so-called "National Assembly" where Mr. Dulles, adviser to the U. State Department, was present: If we cannot protect democracy in the cold war, we shall win in a hot war.

It is not difficult to understand that representatives of the South Korean authorities could only make such statements because they felt that they had American support behind them. One month before the present developments in Korea, on May 19, 1950, Mr. Johnson, chief American administrator of aid to Korea, told the American Congress House of Representatives' Appropriations Committee that 100,000 officers and men of the South Korean Army, equipped with American weapons and trained by the American Military Mission, had completed their preparations and could begin war at any time. It is known that only a few days before the Korean events, the United States Defence Secretary, Mr. Johnson, the Chief of the General Staff of the United States Armed Forces, General Bradley, and the State Department adviser, Mr.Dulles, arrived in Japan and had special conferences with General MacArthur, and that afterwards Mr. Dulles visited South Korea and went to frontier areas on the 38th parallel. Only one week before the events - on June 19 - Mr. Dulles, adviser to the State Department, declared in the above-mentioned "National Assembly" of South Korea that the United States was ready to give all necessary moral and material support to South Korea which was fighting against Communism. These facts speak for themselves and need no comment.

The very first days showed, however, that events were not developing in favour of the South Korean authorities. The Korean People's Democratic Republic gained a number of successes in the struggle against the South Korean troops, which are directed by American military advisers.When it became clear that the terrorist regime of the Syngman Rhee clique, which had never enjoyed the support of the Korean people, was collapsing, the United States Government resorted to open intervention in Korea, ordering its air, naval and subsequently its ground forces to side with the South Korean authorities against the Korean people. Thereby the United States Government went over from a policy of preparing aggression to outright acts of aggression and embarked on a course of open intervention in Korea's domestic affairs, on a course of armed intervention in Korea.

Having taken this course, the United States Government violated peace, demonstrating thereby that far from seeking to consolidate peace, it is on the contrary an enemy of peace. The facts show that the United States Government is only disclosing its aggressive plans in Korea step by step. Then it was announced that air and naval forces, but without ground troops, 2 / 6 03/07/2015 would also be sent.Following this, it was stated also that United States ground forces would be sent to Korea. It is also known that at first the United States Government declared that American armed forces would take part in operations in South Korean territory only. Hardly had a few days passed, however, when the American air force transferred its operations to North Korean territory and attacked Pyongyang and other cities. All this goes to show that the United States Government is drawing the United States more and more into war, but, compelled to reckon with the unwillingness of the American people to be involved in a new military adventure, it is gradually impelling the country step by step towards open war.

The United States Government tries to justify armed intervention against Korea by alleging that it was undertaken on the authorisation of the Security Council. The falsity of such an allegation strikes the eye.

It is known that the United States Government had started armed intervention in Korea before the Security Council was summoned to meet on June 27, without taking into consideration what decision the Security Council might take. Thus the United States Government confronted the United Nations Organisation with a fait accompli, with a violation of peace. The Security Council merely rubber-stamped and back-dated the resolution proposed by the United States Government, approving the aggressive actions which this Government had undertaken.

Furthermore, the American resolution was adopted by the Security Council with a gross violation of the Charter of the United Nations Organisation. In accordance with Article 27 of the United Nations Charter all Security Council decisions on major issues must be adopted by an affirmative vote of not less than seven members, including the votes of all the five permanent members of the Security Council, i. Of the Soviet Union, China, the United States, Great Britain and France. However, the American resolution approving the United States armed intervention in Korea was adopted by only six votes - those of the United States, Britain, France, Norway, Cuba and Ecuador. The vote of the kuomintangite Tsiang Ting-fu, who unlawfully occupies China's seat on the Security Council, was counted as the seventh vote for this resolution. Furthermore, of the five permanent members of the Council only three - the United States, Britain and France - were present at the Security Council's meeting on June 27. Two other permanent members of the Security Council - the U. And China - were not present at the Council meeting, since the hostile attitude of the United States Government towards the Chinese people deprives China of the opportunity of having her legitimate representative on the Security Council, and this made impossible the Soviet Union's participation in the meetings of the Security Council.Thus neither of these two requirements of the United Nations Charter with regard to the Security Council's procedure for taking decisions were fulfilled at the Council's session on June 27, which deprives the resolution adopted at that session of any legal force. It is also known that the United Nations Charter envisages the intervention of the Security Council only in those cases where the matter concerns events of an international order and not of an internal character.

Moreover, the Charter directly forbids the intervention of the United Nations Organisation in the internal affairs of any state when it is a matter of an internal conflict between two groups of one state. Thus the Security Council by its decision of June 27 violated also this most important principle of the United Nations Organisation. 3 / 6 03/07/2015 It follows from the aforesaid that this resolution, which the U.Government is using as a cover for its armed intervention in Korea, was illegally put through the Security Council with a gross violation of the Charter of the United Nations Organisation. This only became possible because the gross pressure of the United States Government on the members of the Security Council converted the United Nations Organisation into a kind of branch of the U.

State Department, into an obedient tool of the policy of American ruling circles who acted as violators of peace. The illegal resolution of June 27, adopted by the Security Council under pressure from the United States Government, shows that the Security Council is acting, not as a body which is charged with the main responsibility for the maintenance of peace, but as a tool utilised by the ruling circles of the United States for unleashing war. This resolution of the Security Council constitutes a hostile act against peace. If the Security Council valued the cause of peace, it should have attempted to reconcile the fighting sides in Korea before it adopted such a scandalous resolution. Only the Security Council and the United Nations Secretary-General could have done this. However, they did not make such an attempt, evidently knowing that such peaceful action contradicts the aggressor's plans. It is impossible not to note the unseemly role played in that whole affair by the United Nations SecretaryGeneral, Mr.Thereby the Secretary-General showed that he is concerned not so much with strengthening the United Nations Organisation and with promoting peace, as with how to help the United States' ruling circles to carry out their aggressive plans with regard to Korea. At a press conference on June 29, President Truman denied that the United States, having launched hostilities in Korea, was in a state of war. He announced that this was only "police action" in support of the United Nations Organisation and alleged that this action was aimed against a "group of bandits" from North Korea. It is not difficult to understand the untenability of such an allegation. It has long been known that, in undertaking aggressive actions, an aggressor usually resorts to this or that method of camouflaging his actions.

Everyone remembers that when, in the summer of 1937, militarist Japan started armed intervention in North China with the campaign on Peking, it announced that this was solely a local "incident" for the sake of maintaining peace in the East, although no one believed this. The military operations which General MacArthur has now undertaken in Korea upon the instructions of the United States Government can be regarded as "police action" in support of the United Nations Organisation to just the same extent as the war started by the Japanese militarists against China in 1937 could be regarded as a local "incident" for maintaining peace in the East. As is known, the operations of the United States armed forces in Korea are commanded, not by some police officer, but by General MacArthur. However, it would be absurd to admit that the Commander-in-Chief of the United States Armed Forces in Japan, General MacArthur, is directing, not military operations, but some sort of "police action" in Korea. Who will believe that MacArthur's armed forces, including military aviation, down to "Flying Fortresses" and jet planes, which attack the civilian population and the peaceful cities of Korea, the navy, including cruisers and aircraft carriers, as well as ground forces, were needed for a "police action" against a group of bandits.

This is something that even quite naïve persons will hardly believe. 4 / 6 03/07/2015 It will not be superfluous to recall in this connection that when the People's Liberation Army of China was fighting against Chiang Kai-shek's armies, which were equipped with American military technique, certain people also called it "groups of bandits". What the reality turned out to be, however, is something wellknown to all. It turned out that those who were called "groups of bandits" not only expressed the fundamental national interests of China, but also constituted the Chinese people.Those whom the ruling circles of the United States thrust upon China as a Government turned out to be in reality a handful of bankrupt adventurers and bandits who traded the national honour and independence of China right and left. What are the real aims of American armed intervention in Korea?

Evidently, the point is that the aggressive circles of the United States violated peace in order to lay hands, not only on the South, but also on North Korea. The invasion of Korea by American armed forces constitutes open war against the Korean people. Its goal is to deprive Korea of her national independence, to prevent the formation of a united democratic Korean State and forcibly to establish in Korea an anti-popular regime which would allow the ruling circles of the United States to convert the country into their colony and use Korean territory as a military and strategic springboard in the Far East. In ordering the United States armed forces to attack Korea, President Truman at the same time stated that he had ordered the American Navy "to prevent any attack on Formosa", which means the occupation by American armed forces of this part of China's territory.This move of the United States Government constitutes outright aggression against China. This move of the United States Government furthermore constitutes a gross violation of the Cairo and Potsdam International Agreements concerning Formosa being Chinese territory, agreements which bear the signature of the United States Government too, and is also a violation of the statement made by President Truman on January 5 of this year to the effect that the Americans would not intervene in the affairs of Formosa. President Truman also stated that he had instructed American armed forces to be increased in the Philippines, which aims at intervention in the domestic affairs of the Philippine state and at kindling an internal struggle. This act of the American Government shows that it continues to regard the Philippines as its colony and not as an independent state, which, furthermore, is a member of the United Nations Organisation. President Truman stated in addition that he had issued an instruction that so-called "military assistance" to France in Indo-China be accelerated.

This statement of President Truman shows that the United States Government has embarked on a course of kindling war against the people of Viet Nam for the sake of supporting the colonial regime in Indo-China, thereby demonstrating that it is assuming the role of gendarme of the peoples of Asia. Thus President Truman's statement of June 27 means that the United States Government has violated peace and has gone over from a policy of preparing aggression to direct acts of aggression simultaneously in a whole number of countries in Asia. Thereby the United States Government has trampled underfoot its obligations to the United Nations in promoting peace the world over and has acted as a violator of peace. There is a small number of historical examples of cases where, by means of intervention from without, the attempt was made to throttle the struggle waged by the peoples for national unity and for democratic rights. In this connection one could recall the war between the Northern and Southern States of North America in the sixties of the last century.

At that time the Northern States, headed by Abraham Lincoln, waged an armed struggle against the slave-owners of the South for the abolition of slavery and for the preservation of the national unity of the country. When attacked by the South, the armed forces of the Northern States did not, as is known, limit themselves to defence of their own territory, but transferred military operations to the 5 / 6 03/07/2015 territory of the Southern States, routed the troops of the planters and slave-owners, who did not enjoy the support of the people, smashed the slave-owning system existing in the South and created the conditions for establishing national unity. It is known that at that time certain governments, as for instance the British Government, also intervened in the internal affairs of North America in favour of the South against the North and against national unity. Despite this, victory was won by the American people as personified by those progressive forces which headed the struggle of the North against the South. It will not be amiss to recall also another lesson of history. In the period after the October Revolution in Russia, when the reactionary tsarist generals, having dug themselves in on the outskirts of Russia, rent Russia asunder, the Government of the United states, together with the Governments of Britain, France and certain other States, intervened in the domestic affairs of the Soviet country and came out on the side of the reactionary tsarist generals in order to prevent the unification of our Motherland under the aegis of the Soviet Government. The United States Government also did not shrink from armed intervention, sending its troops to the Soviet Far East and to the Archangel area. Together with the troops of certain other countries, the American troops actively helped the Russian tsarist generals - Kolchak, Denikin, Yudenich and others - in their struggle against the Soviet power, shot Russian workers and peasants and plundered the population. As we see, in this case too, the ruling circles of certain foreign states, violating peace, tried by armed intervention to turn back the wheel of history, tried forcibly to impose on the people the much-hated regime they had overthrown and tried to prevent the unification of our country into a single state.It is universally known how this interventionist adventure ended. It is useful to recall these historical examples because the events now taking place in Korea and certain other countries of Asia, and the aggressive policy of the United States as regards these countries, are in many respects reminiscent of the above-mentioned events from the history of the United States and Russia.

The Soviet Government has already expressed its attitude towards the policy which is being pursued by the United States Government, a policy of gross intervention in the domestic affairs of Korea, in its reply of June 29 to the statement of the United States Government, dated June 27. The Soviet Government invariably adheres to a policy of strengthening peace the world over and to its traditional principle of non-interference in the domestic affairs of other states. The Soviet Government holds that the Koreans have the same right to arrange at their own discretion their internal national affairs in the sphere of uniting South and North Korea into a single national state as the North Americans had in the sixties of the last century when they united the South and the North of America into a single national state. From the aforesaid it follows that the Government of the United States of America has committed a hostile act against peace and that it bears the responsibility for the consequences of the armed aggressions it has undertaken.Address by the Soviet Representative (Andrei Gromyko). To the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission. Address delivered at the second meeting of the Commission. The Atomic Energy Commission created in accordance with the resolution of the Moscow. Conference of the Foreign Ministers of the Three Powers1 and with the resolution of the.

First session of the General Assembly, 2 must proceed to the practical realization of the tasks. The significance of these tasks and, consequently, of the activities of the. Commission, is determined by the importance of the very discovery of methods of using. Atomic energy, which led to the creation of this Commission.

Produced a result, the significance of which is hard to appraise. Known regarding the significance of this discovery and which, undoubtedly, is merely the.

Preliminary to still greater conquests of science in this field in the future, emphasizes how. Important are the tasks and activities of the Commission. As the result of the definite course of events during the last few years the circumstances. Were combined in such a way that one of the greatest discoveries of mankind found its first. Material application in the form of a particular weapon -- the atomic bomb.

Although up to the present time this use of atomic energy is the only known form of its. Practical application, it is the general opinion that humanity stands at the threshold of a. Wide application of atomic energy for peaceful purposes for the benefit of the peoples, for.

Promoting their welfare and raising their standard of living and for the development of. There are thus two possible ways in which this discovery can be used.

One way is to use it. For the purpose of producing the means of mass destruction. The other way is to use it for.The paradox of the situation lies in the fact that it is the first way that has been more. Studied and more effectively mastered in practice. The second way has been less studied. And effectively mastered in practice.

However, this circumstance not only does not. Diminish the importance of the tasks that lie before the Atomic Commission but, on the. Contrary, emphasizes to an even greater degree the significance of these tasks for all that. Concerns the strengthening of peace between the nations. 1 Moscow Communique by the Foreign Ministers of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet.2 General Assembly Resolution 1 (1): Establishment of a Commission to Deal with the Problems Raised by the. Discovery of Atomic Energy, January 24, 1946. There can be no active and effective system of peace if the discovery of the means of using. Atomic energy is not placed in the service of humanity and is not applied to peaceful.

The use of this discovery only for the purpose of promoting the welfare of. The peoples and widening their scientific and cultural horizons will help to strengthen. Confidence between the countries and friendly relations between them. On the other hand, to continue the use of this discovery for the production of weapons of. Mass destruction is likely to intensify mistrust between States and to keep the peoples of.

The world in a continual anxiety and uncertainty. Such a position is contrary to the. Aspirations of the peace-loving peoples, who long for the establishment of enduring peace. And are making every effort in order that these aspirations may be transformed into reality.As one of the primary measures for the fulfilment of the resolution of the General Assembly. Of 24 January 1946, the Soviet delegation proposes that consideration be given to the. Question of concluding an international convention prohibiting the production and.

Employment of weapons based on the use of atomic energy for the purpose of mass. The object of such a convention should be the prohibition of the production. And employment of atomic weapons, the destruction of existing stocks of atomic weapons. And the condemnation of all activities undertaken in violation of this convention.Elaboration and conclusion of a convention of this kind would be, in the opinion of the. Soviet delegation, only one of the primary measures to be taken to prevent the use of. Atomic energy to the detriment of mankind. This act should be followed by other measures. Aiming at the establishment of methods to ensure the strict observance of the terms and.